God’s Loneliest Men - A short story

Words by Simra Sadaf

Illustrations by Kairav Trivedi

The Calcutta Killings

September 22, 1947

Pyaaray Saaim,

You haven’t written any letter since reaching Lahore. Do you miss your home back in Calcutta? By home, I mean Hindustan. I am sure you don’t miss the street violence and civil war, but do you miss sneaking up to my terrace after midnight so you can meet me and listen to my poems and dastaan? Some part of me wants to run to your country barefoot and recite my new poem to you. This one is not about you or your knuckles or my undying devotion to your gentle being, I swear. This one is in memory of your father. He didn’t deserve to die that way. None of them did. My naani curses the angrez every day. She says they raided us with their mouths full of gasoline and tongues like matchsticks. She makes us pray for everyone who lost their lives in the Calcutta Killings. We pray for your father every day, and I pray for you after every azaan like you taught me to. I pray that I would wake up one day and find you standing on my chaukhat with a paper cut-out of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s new ghazal and I would run to my room and hide it under my pillow.

We screamed, fought and died for freedom, but I feel more trapped than ever. I imagined the cage you left me in would be bigger, but it’s smaller than my rib cage. Saaim, there are times I wonder if I have given enough to the things I love —words, my writings, my grandmother, and to the stories I dreamt and forgot upon waking up. Amma has forbidden me from reading and writing. She hates writers. She calls us “a waste of space”. Yesterday I reminded her that my father, her husband, is also a writer. Just the zikr of him made her face look like it was carved out of stone. She laughed and said “Wahi toh. Waste of space. Shouldn’t have married a writer, upar se Ek musalmaan writer” and laughed harder. She isn’t handling the pain of losing her husband very well. I miss him, Saaim. If you meet him in Lahore, ask him to reply to my letters. I know he is mad at me and Amma for staying back, but we couldn’t leave naani here. She says she was born here and would die breathing Calcutta’s air.

I know you will burn the letter as soon as you finish reading it, but don’t burn the ghazal I’ve pinned with this letter. It is by Faiz:

“Donon jahaan teri Mohabbat mein haar ke, vo ja raha hai koi shab-e-gham guzaar ke.”

Saaim, they wrote poetry to voice against oppression. One day, when I have enough guts in my fingers, I will write for our love, and fight with everything I have got —a few pale pages, your white pathani suit, and god-fearing strokes of ink. I promise you we will see a day where we don’t have to hide our love like I hid Manto Ke Afsanay on the backside of my desk, where the agony in our chests should only be about the lives lost fighting against the British and not the fear of dying as God’s loneliest men. Write back. Please.

Yours,

in this life and thereafter,

Rana.

Trails of Separation

October 19, 1947

Dearest Rana,

Salaam. How are you? I was busy setting up the new house. We are all fine here. None of us has any work yet. We have been promised a job when the cotton mill reopens by the end of next month. Your baba is staying with us. On most nights, Ammi and I hear him crying, but we don’t console him. We just hear his muffled cries and go to sleep like we don’t miss our home or family and friends. But last night, he cried for two hours straight, so I knocked on his door and asked if he would like to have chai or shahi tukray that Ammi made for dessert.

Unlike your Amma, your baba is handling his pain with a beedi stuck to his lips at all times and his spine in the cradle of a wooden chair. He reads the newspaper every day, not to read about Jinnah or Nehru, but to read what poem and story have been published that day. And then he settles in to do nothing for the rest of the day. He hasn’t opened any of your letters yet. Maybe he’s scared the weight of your words would crush his existence.

I noticed you wrote to me on your birthday. Belated birthday wishes, Rana. Did you visit the temple like you usually do every year? You know when we were walking away from India, I felt like scraping the heel of my foot with a blade so it would leave blood trails for historians to study the magnitude of my anguish, or for tourists to take pictures and call it “Trails of Separation.” Going by the ache in my chest, I think I would become a poet before you. Khair ye baatein rehne do. Why don’t you send me your writings instead of Faiz or Ghalib’s? And I miss naani’s bantering. Hug her a minute longer for me, will you? Do you remember our first meeting, Rana? You had just moved to Calcutta from Bombay. You had school-boy hair and a smile I had never seen before.

You were the tallest boy in our class. Razia used to have a crush on you that’s why she did your math homework almost every day. It annoyed me how she was so open about her feelings when I had to hide my love from Abbu’s fists, but your baba always knew you loved me. I just want to sink into your arms while drinking nimbu paani and listen to the sound of your voice that breaks each time my fingers graze your thighs. I wake up every day in a country I didn’t choose to be in. I can’t claim this country as mine, and I can’t claim India as mine either. My thoughts and soul still lives in the streets of Calcutta, playing cricket after school. They’re all just memories now, and I am nothing without them, without you.

Ammi says I never laugh anymore, how do I tell her I left my laughter in the corner of your eyes? Kis kis ko bataaenge judaai ka sabab hum, Rana? I am tired. Aren’t you?

Yours,

Saaim.

A Man’s Umbilicus

November 5, 1947

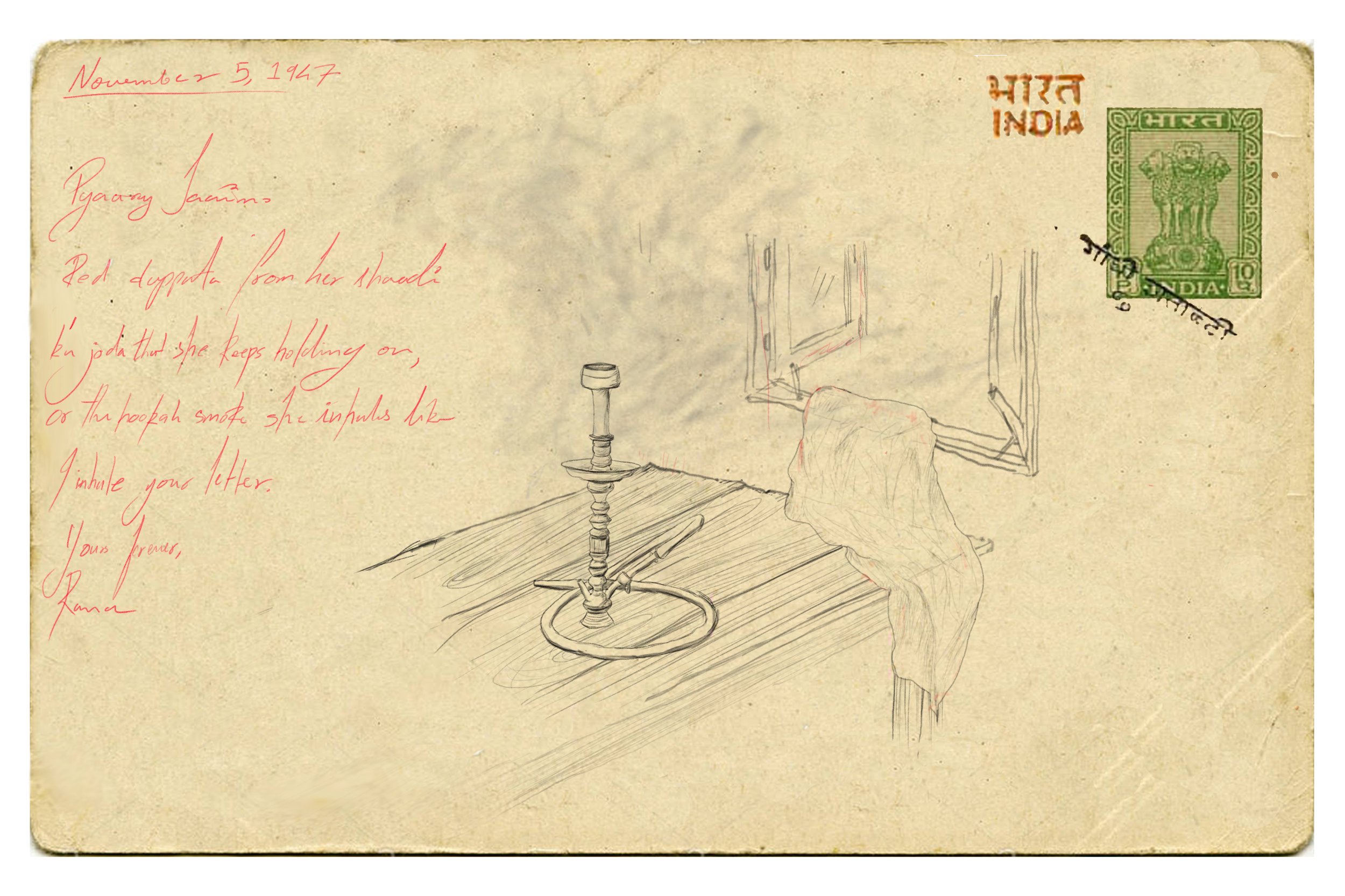

Pyaaray Saaim,

Kitni uljhi baatein likhi hain tumne. Mere lafz saada lag rahe hain ab toh. And I call myself a poet! I saw Baba in my dreams a few nights ago. He asked me if Amma erased him from the sheets of their bed and rinsed herself off the lingering tobacco smell. Tell him she didn’t, but her once gentle hands have become raw from all the slaps to my cheek after I told her I want to become a writer. Don’t worry, it stopped hurting after the second slap, bas unki chaar ungliyaan gaal pe saji rehti hain. I don’t know what will kill her first —baba’s aura that never leaves our aangan, or the red dupatta from her shaadi ka joda that she sleeps holding. Or the hookah smoke she inhales like I inhale your letter. Tell baba I will never erase him either. Tell him I carry his lullabies, his whispers, his teachings of the Quran, and his nazmein everywhere I go.

There is something you need to know. Naani passed in her sleep a week ago. We cremated her near the Ganga ghats. We don’t know what to do with her ashes yet. I want to scatter it in the air because that’s what she would have wanted, to live forever in Calcutta’s breeze. Ask baba to pray for her maghfirat, Saaim. Just like you said you are torn between two nations, I am torn between two religions. Baba used to say prayer is hope and God is home. Sometimes when Amma is asleep, I run upstairs and prostrate in the brown prayer mat you left behind in my terrace. I am a product of two strong believers. I’ve grown up celebrating Krishna’s birth and fasting and celebrating Eid. But my Eid has always been you, Saaim.

The night before Naani breathed her last, I hugged her for you, told her I loved you more than life itself. She shoved her husband’s prejudiced words down my trachea. She said “even before a man’s umbilicus is severed, he is expected to clench his fists, hold his tears back, and sharpen his nose like a sword”, then she looked at my tears and neglected it the way God has been neglecting the fire that’s burning the insides of my stomach, and said, “mard ban jao thoda.”

Yours forever,

Rana.

A Frozen Turkey

January 3, 1948

Dearest Rana,

I am so sorry for your loss. I am sure God will grant her the highest place in heaven. I wish I was there to wrap my fingers around your wrist and calm your hammering pulse, but please know I am here to share your grief. If you ask me, I think you should grow a tree with her ashes, like a tree urn, and by that way, she’ll continue to live and breathe. I started working at the cotton mill and your baba teaches English at the government school. I work as a finisher. I roll, fold and wrap the cotton. By the end of the day, my legs are numb like a frozen turkey, and for what? Two rupees. Anyway, what are you doing these days? Are you planning to study literature? I hope you do because your baba says he used to whisper Alfred Noyes’ The Highway Man in your ears to calm your cries. You are made of words, Saaim. I am sure your Amma will understand the passion you have for storytelling.

I made a friend here at work. I’ve been spending a lot of time with her as we see each other every day. Her name is Sultana. She is funny and mimics the executive manager when he’s not around picking faults at literally everything we do. I wish you could meet her. She says poetry is a blend of lovesickness and homesickness that makes a writer house a cemetery, cave and a cathedral in his sternum. Two years ago, you wrote a story about a nomad who conned people wherever he went by saying he was a professional palm-reader. The nomad would say distressing things about their future and scare his customers so they would live in fear for the rest of their lives. This is exactly how I feel about my future, except you are the nomad who didn’t just read my palm but also inscribed yourself in its lines.

I have trudged through the expanse of leaving myself in you and trying to find myself in an unknown city where men judge women on the length of their burqa. These days, I find myself mirroring you, your anger and your hostility towards the partition. I read the books you love, drink coffee the way you would —dark and bitter.

Rana, I have something to tell you. After your baba got that teaching job last month, he and Ammi got married. It was a small Nikaah with only me and a Qazi present. Believe me, I am fighting with my conscience the entire time I am penning this letter. I wanted to hide this from you so there could be no hindrance to our love, but my heart couldn’t bear the thought of keeping you in the dark and betraying your trust. More than the distance between us, for me, your baba marrying Ammi has blocked all the roads I could have taken to your home, your heart and your homeland. Do you think this has shut the door on the possibility of us reuniting one day?

Awaiting your reply.

Yours,

Saaim.

Shades of Red

January 27, 1948

Dear Baba,

Congratulations on your wedding. I hope you’re happy. I do. After all, how long can a man battle loneliness and separation? I told Amma you got married. She wordlessly suffocated her anger and smiled at me, but I could see her heart breaking into a hundred different shades of red and staining her hairline. We are moving to Bombay next week for my further studies. Amma wants me to become a lawyer and I’ve decided to pursue it. I know you wanted me to be a writer like you but I don’t want to disappoint the only parent I am left with. The one who still combs my hair and tells me she’ll never leave me. Disappointing you is a burden I can live with, but hurting her will feel like I have a noose tied around my neck at all times. Please congratulate your wife on my behalf and give her all my love.

It’s funny how God snatched you from me and put you in Saaim’s lap. Is he happy to have you as a father? I know he is. He always looked up to you even when his father was alive. Remember the day he was beaten to a pulp for talking back to him? He cried and cried till he choked on his yelp. He must worship you now. They say if you are desperate for something, you tend to make a God out of it, and boy was he desperate for a good father! Tell him I won’t write to him anymore. It’s not the distance. It’s everything that came with it —the trauma of losing you, his letters hinting a tone of condescension (or maybe it’s just my bitter-self) and most importantly, acceptance; people’s taunts would chip away at my sanity, and I’ve already lost my peace once. The noose would get tighter if I lost it again.

I don’t want to live with the fear of someday finding myself drowning in my own blood like Ajay from school. What was his fault? He loved a man and they broke his bones in the name of honour. This is how they taint something pure. They taint it with blood and shame and disgust. Naani told me to become a man. If becoming a man means half repression and half arrogance then I am sure I can become a better man than you. Amma insists I visit the temple one last time before leaving Calcutta. How do I tell her I am not a religious person anymore? I tried to make it clear by ignoring her pleas but you know how stubborn she can get. She has packed four shirts of yours that you left behind as she knows the feeling of abandonment too well and she wouldn’t wish that even upon her worst enemy. I love you and this is my last letter to you. Please cherish it.

— to all those unwritten stories.

Your son,

Rana.