Dear Mother

From the Editor’s Desk

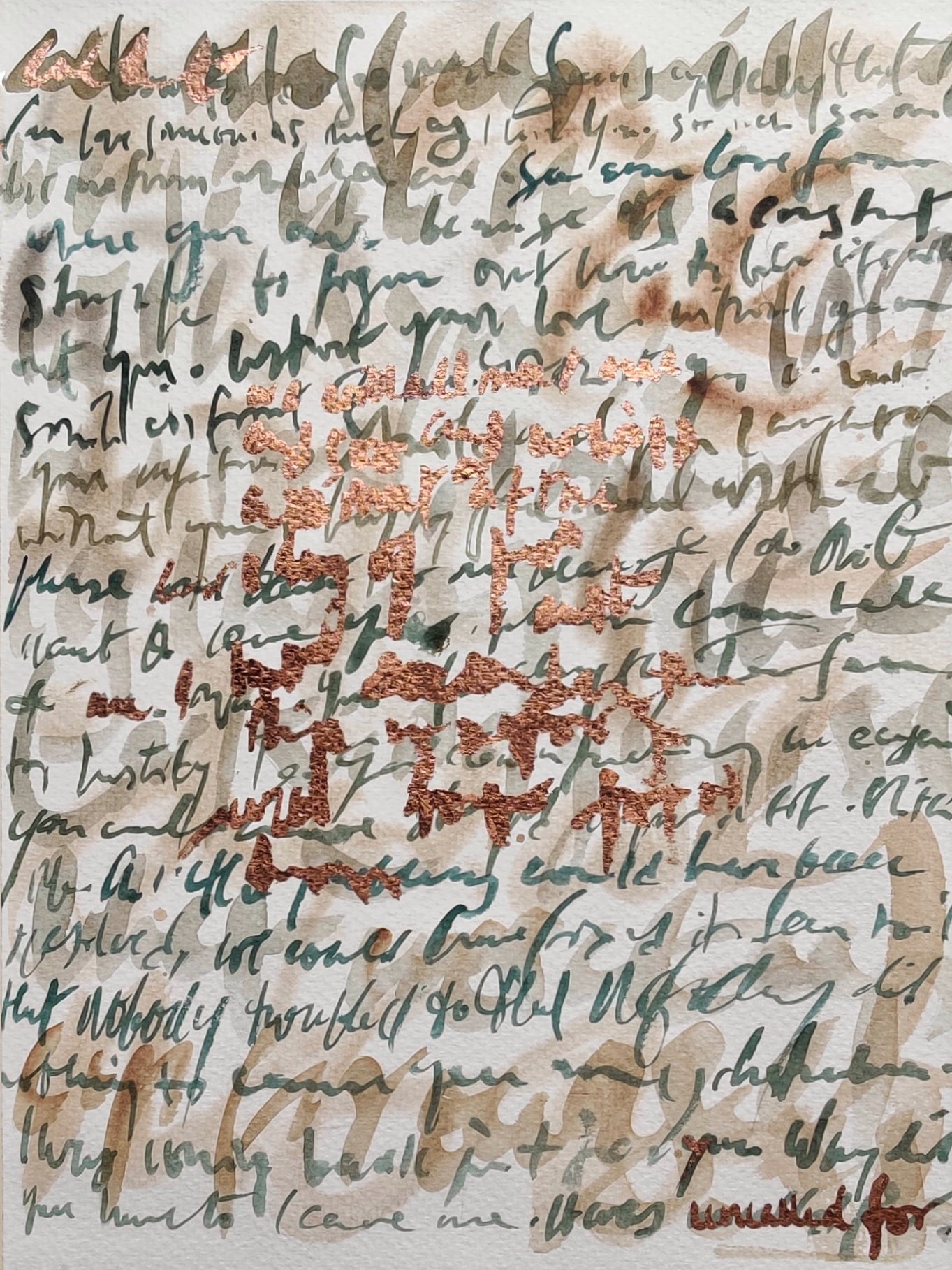

There is a sense of serenity that befalls anyone who comes across Al-Qawi Nanavati’s work. They reek calm and sensibility while having an exciting secrecy to the entire ensemble. You want to understand what is going on but instantly are distracted by the beauty of its cryptic nature. It is a fitting reflection of Al-Qawi’s deeper sense of her consciousness, her soul, if you will. Amongst all her works, the most profound of all that spoke to me as well as to many was the one titled ‘Letters to my mother.’

Every artist has a defining moment or an occurrence that shapes not just their personality but their work as well. That defining moment could be a worldy happening like a war (George Baselitz), social injustice or something very personal like Sylvia Plath’s husband leaving her.

For Al-Qawi, it was the passing of her mother.

“My mother and I would have a conversation every day, especially when I moved to Chicago for my higher education. We would be on call when I was in college, in the mornings when I would get ready, when I would walk to class. I’d call her during lunch but she'd be asleep and she'd call me after she woke up. After my college, I had to move to another building which was further away from where I was working. It would take about a good half an hour to commute to anywhere. I spoke to her every single day on my bus ride to work, and it became a routine. If you are wondering what we would talk about so much, it was about the most mundane of things. I hardly remember those conversations, it would be very random and it was a very normal thing to do, something we made an effort to.

March 2018 was the last time I spent with my Mom. Around that time, I had started work on a series called ‘33 Days of Ibadat’ - 33 Days of Prayer. 33 is the number of beads that are there in our prayer bracelet. I had taken up waking at 4:00 in the morning to practice Bandagi where you pray and meditate for your peace and sanity. I had spoken about this to my mother, and her encouragement kept me going. So, I started doing this whole painting series. I kept making paintings about death and the afterlife which was very odd. I used to talk to my Mom about it, and shared with her my thoughts and feelings. As I started doing this series, I kept making art about death and the afterlife which was very odd to me.”

“I finished the series and 2-3 days later, she passed away. It was very shocking, uh, I mean you think your parents will die and eventually they will, but you just don’t expect it.”

This very “odd body of work” gave Al-Qawi the “weird, unknown” strength and realisation that death is okay. Having a conversation about death with her mother was an eye-opener and the defining moment.

“I had so much to write, I had just spoken to her for about four hours before she passed away. And I was the last person that spoke with her. I chose letters because we spoke every single day, even when she was in the hospital. We never skipped a phone call, unless one of us left a little early, or woke up late. It became one of those things where I had lost someone I was speaking to every single day of my life. All of it is just a conversation between me and her, except now it’s one-sided.”

A Picture of Her Mother

“My mother was tall with salt and pepper hair. She never coloured it. Although, she took efforts to maintain it. There’s a shampoo that she uses for her greying hair which made it shine, look silver even, and distinct. She had a bob-cut for a very long time and then she went to this very graduated short bob. She always surprised me with her spontaneity. Once she went for a haircut when she came to visit me in Chicago, and out of nowhere she had this brand-new hairstyle. It was sleek and chic, I would never be able to pull it off!

Growing up, my mother was never strict with my education, but she made it a point to subtly remind us of what would happen if we didn’t study well. I found her approach to this very interesting. It was like she was pulling a reverse psychology trick! I had always known her to be fun-loving. She was a voracious reader – she had a library filled with books, and there was no stopping her once she started reading. Eventually, we ended up having to buy her a Kindle.”

Letters to my Mother, 2018

Al-Qawi’s artwork includes several forms of art – printmaking, embroidery, weaving, crocheting. She enjoys going with the flow and works with whatever feels right in the moment. She says that she has been using her mother’s old clothes to create those letters. “My mother loves clothes. I still have hers, I haven’t given those away. I also stopped buying clothes, I only wear her clothes now. If I want new clothes, I’ll go to her cupboard and get them sized.”

The language that we share with our mothers is very unique. Mothers understood us even when we couldn’t spell words, they felt our needs before we even asked for them. It would even be safe to say that mothers and children share a sacred language spoken only by the two of them. It only made sense for Al-Qawi to keep in touch with her mother as her child that way. “It would have to have a name only if someone else had to know it. It’s between my mother and I, no one else has to know it.”

Her mother’s affable nature made it easy for the two of them to naturally fall into conversation, so easy that they spoke every day! Juggling between college classes and work, Al-Qawi made it a point to keep up with the routine with whatever time she would get - while commuting, on the bus, walking. Their companionable relationship provided space to talk of the mundane, their lives and everything in between.