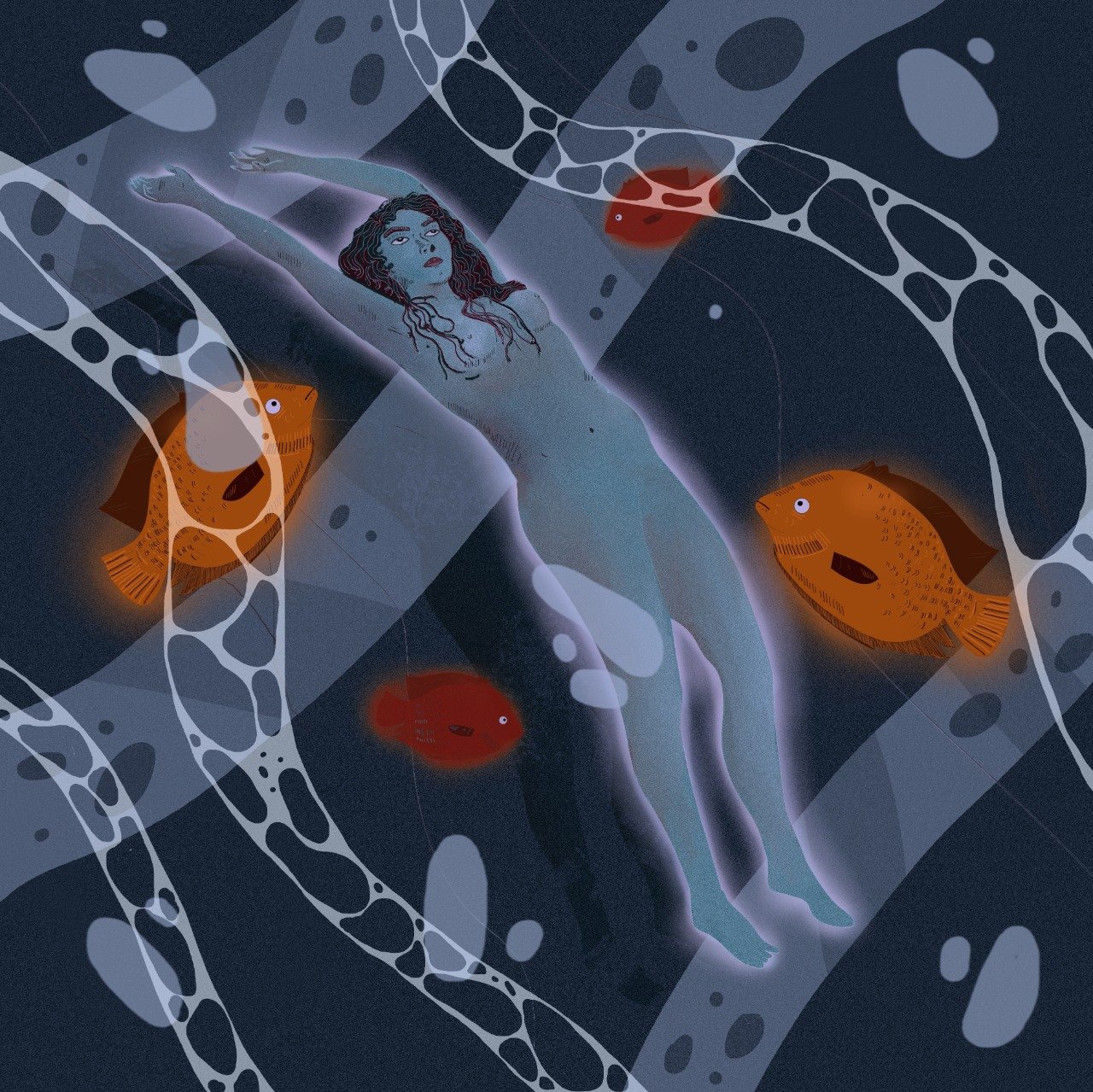

Dead Swimmers

Annalise ate biryani for breakfast while Arimbadu was still sleeping.

Her father had come back home yesterday after seven years. Arimbadu Varghese was told over the telephone that his little girl had grown up; she was no longer his partner in fish-eating, and in mango-picking. She had long hair now, still curly, and it reminded him of how she would ask him, at age five, to tie stones at its ends so that they may straighten. She had gotten the idea from a serial her grandmother was then watching about St. Alphonsa. When the man who tried to kill Alphonsa realized his mistake, he went to the river overcome by guilt, tied a rock to his neck, pulled it across the river bank and into the river, and drowned. Annalise understood then, that if you tie stones to things, they will go down - a solution to a problem pervading her life of five years. So she had asked Appa to help.

Arimbadu had left home when Annalise was ten. A garment factory in Dubai was recruiting workers, and he had decided to leave, because there wasn’t much to do even if he stayed. ,Annalise would, from then on, learn to know him through the telephone receiver, catching his voice and the many dribbles in it, and learning, from the way it moved, to love herself through him. Her father had grown up in Kainakary, a small village nestled in the backwaters of Alleppey, where the rice fields in the backyard looked out at the river, and the palm trees never tired from whistling. He had left after finishing his degree to Hubli, where he got his first job and met the love of his life, Catherine. Hubli was where Annalise was born and where she grew up. But she had never seen summers in Hubli. Every year, during summer break, they would leave, back to the house on the banks of the Pamba.

It was as if she had shared a childhood with Arimbadu in Kainakary. As if she had had two fathers - one in Hubli, and one in Kainakary. And of course, a third one living in heaven. Jesus. The sisters in church would sometimes say Jesus was her father, and some other times, that she was his bride. But she didn't want to be married.

Each time they arrived, her grandmother would prepare a feast.

There would be the Karimeen fry - Pearlspot deep fried until crispy in a mix of red chilly powder, tumeric and strong pepper. There would be the duck curry, which tasted more like potatoes than duck. And the three kinds of fish: the choora - tuna steeped in a vermillion gravy made of crushed red chillies and sour tamarind, a mathi peera - sardines in grated coconut and turmeric, and the meen manga curry - Sole fish floating in a dense gravy of ripe mangoes and coconut. Three different kinds of dead fish swimming in the earthen pots of Kainakary. Would fish die if stones were tied to their necks? Fish had no necks, so no.

When, in their house in Hubli, Mummy would cut the heads off of Anchovies to fry them for lunch, Annalise would sniff, and run her hands through the silver fish. Running, she would go to Arimbadu to make him smell it. ‘This is the smell of Kainakary soil, Appa!’ Together, they would smell her tiny hands with glee.

Mummy was mostly an outsider in this coterie. In the years that Arimbadu was gone, she would remember bits of him to keep herself entertained - the way he spoke Hindi - slowly, brokenly, but never giving up; the way he always stained his shirt while eating and then acted like he didn’t see; the way he looked at her coming out of church on Sunday mornings, dressed in a saree. In the mornings, she would think of his fingers traipsing over her forehead, to the beat of an old Malayalam song he would sing:

Suryakanthi, suryakanthi, swapnam kaanuvathaaro

You, a sunflower, who are you dreaming of?

Annalise and Catherine had more in common than they imagined; their lives were a constant recollection of old memories - a record playing on loop, trying to conjure up the person they both loved so much.

Catherine had taught her things Arimbadu would be pleased to know she knew. They were as follows:

To always know who E.M.S Namboodiripad was, and to know who V.S. Achuthananthan was. Or to act like she knew, when he was talking.

To always take a leave from school once each year on the day of the Kerala boat race and cheer for team Kainakary.

To know that the government was a bad-bad thing. And that they would come for her one day. She was not to care when they did.

To read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky when she grew up, two men her father found in the Marxist library at Alleppey town where he went with his friends after school on Fridays. She had thought the name sounded friendly. Dost meant friend in Hindi.

She also learnt the songs he listened to on his radio, sitting on the terrace in the evenings. Her favourite was the one she had heard comrades sing at Marxist rallies.

Balikudeerangale..Balikudeerangale..

Smaranakal irampum ranasmarakangale

Ivide janakodikal chaarthunnu ningalil

Samarapulakangal than sindoora maalakal..

It would always make her smile. The other favourite was the song sung at Christian funerals - the one she was forbidden from singing out aloud while playing with her cousins. Everyone knew everyone in Kainakary and someone was always dying. She thought it was unfair that such a beautiful tune was designated to a funeral song; one she wouldn’t have the privilege of singing many times. Except, in Kainakary.

Annalise loved everything about Kainakary except for its hens. They ran behind her everywhere - in the house, in the kitchen, on the front porch. She would wake up to see them hiding under her cot bed, hatching eggs and plans to harm her, in the warmth of her shadow. In those days, she believed in God and prayed to him to kill all the hens in the house. So that she wouldn't have to be careful when she walks around or goes out to play. So that she wouldn't have to wake up in fear every morning. Just kill them, Father Jesus, just kill them.

On one of those days, her grandmother decided she was bored. Annalise's elder cousin, Tiby, was called and told to do the needful. Annalise saw him running behind a hen. At first, she thought it was to feed it. It went on for a while and when both Tiby and the hen were tired, one of them gave up. The loser's legs were tied together. A large tub was brought into the front yard and was filled with boiling water. Annalise stood watching, not knowing the things that were about to happen. In front of her eyes, the hen was plopped into the water.

A loud rally of cackles. A Marxist strike in the house. Lal Salaam, Comrade Henny.

When it registered in her mind, she stopped breathing. God made her wish come true. No, she didn't want this. This was wrong. Silence the hen, Father God. Make it come out of the water, she prayed.

That day she learnt that things once prayed for cannot be unprayed for. She was no longer Anna-mol from Hubli, master fish-eater of Kainakary. She was a praying witch, the murderer of hens, the silencer of cackles.

She sang the funeral song for Henny, the dead hen that swam in the hot water.

Samayamam rathathil njan

Swargayathra cheyyunnu

Nin pradesham kanuvanai

Njan thaniye pokunnu.

In the chariot of time,

I am making my way to heaven.

To see your house, Lord

I am coming alone in haste.

Lesson one: When something died in Kainakary, it floated in its water.

From the debris of what died in her that day, other things grew. Her triumph had surpassed guilt.

Lesson two: If she hated someone enough, they could die.

By the time the chicken was on the table for dinner, she was chewing into it with rage, tearing the flesh apart to kill it one more time. How dare it scare her. She was in control now. All hens, beware.

Lesson three: If someone she hated died, she could eat them. Like they ate away at her peace. Since that day, chicken has become her favourite thing to eat.

So when she got news of her father coming back, she prepared quickly to make him a meal - the famous Kainakary chicken biryani. Mummy had gladly gone to the market and after much haggling, got a kilo of chicken home. Annalise had laughed when she read a dialogue in Bernadine Evaristo's book 'Girl, Woman, Other' about a woman named Bummi who tells her daughter - "why pay a pound for a pound of apple when you can get them for less if you stand your ground and outtalk the market trader until they are so vanquished they will practically give them to you for free just to get rid of you? With such savings accumulated over time, you can purchase a whole chicken if you similarly haggle with the butcher". Bummi and Mummy were quite alike.

In the evening, by the time the doorbell rang, Annalise had practiced many times over how she would run to her father and hug him. Her shoulders couldn’t contain the happiness. As she opened the door, arms wide, he dashed in, eyes sunken, shaking.

"Annalise, can you turn on the tv?"

"What happened?", she asked, bewildered.

A flood had hit Kerala. The water her father had trusted so much and the God Annalise prayed to, had wrecked their home. Kerala had received an alarming amount of rain over the past month and the gates of the Idukki dam had been let open now, allowing the water to pass through from the hills to the low lying planes. One of the most affected parts - Kainakary. On the TV screen, images of broken homes and arms peeking from under the debris flashed. All the hens in the Kainakary house had died. Dead things swam in the water on TV. Hens, fishes, cows even. And people.

Lesson four: Never pray to God.

Things once prayed for cannot be unprayed for.

She stood in silence, a song playing through her head.

Samayamam radhathil njan

Swargayathra cheyyunnu..

In the chariot of time I am making my way to heaven.